Conversation with Libby Werbel

A conversation with Libby Werbel.

I had the pleasure of sitting down with Libby Werbel, founder and director of Portland Museum of Modern art, an exhibition space located in the stairwell and basement of Mississippi Records in Northeast Portland, Oregon.We talked about our experiences as young adults living in the Southwest, the role of arts administrators, and about the current and upcoming programming at PMoMA.

Jodie Cavalier: I read that you are an Oregon native and spent time in New York City before coming back to live in Portland, Oregon…

Libby Werbel: No. I’ll give you the long story. I grew up in NE off of Glisan. When I left I went to a Liberal Arts School that doesn’t exist anymore in Santa Fe, New Mexico.The college has officially closed.. Once I graduated I moved to Fruitvale in Oakland and then moved to SF about a year later. I lived in the Bay Area for four years total. I loved it there.It was like pretty magical in SF at that time. I think it was also just the best window of my adulthood. I lived in the Mission and worked at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts as an art handler.

At some point I reckoned with the fact I wasn’t done living in other places and if I stayed in San Francisco I might not ever leave so I moved to Barcelona for a year on a whim. I mean not on a whim. It was planned, but I didn’t have a job lined up. I wanted to spend time there and I had a community. I was living there illegally and I was broke so I ended up cleaning people’s houses and bagging candy at a shop and eventually thought, ‘ya know, I’m a college educated woman scrubbing floors for 5 euros an hour and I should probably go back home’. I stopped in New York on my way back since it was the cheapest ticket and although I thought I was only going to be there for a week, I ended up there for a year because I kept getting all of these museum jobs.

JC: What do you remember of the Portland community before you left in the 90s?

LW: It’s actually why I left. I felt I was never going to get access to any contemporary art culture in Portland if I stayed here. It wasn’t that I was a very well versed kid in the arts, but I knew that Portland for all of its glory, was limited. Which it was, and even though I felt very attached to Portland when I left, I knew I needed to access other cultural outlets. And Santa Fe was the art school that accepted me. [laughter] The reason I attended the College of Santa Fe was actually due to my interest in St. John’s College which is another college in Santa Fe. Their whole program is based on just reading the great books. It's all the great books and that's it. Four years of reading and dialogue. That school is infamous. I was interested in film and photo at the time and they didn't have an arts program. I knew that I needed a hands on visual arts practice while in college and I had gotten my mind set on a desert landscape… so Santa Fe and then the Bay Area.

JC: What experiences from those places (landscapes and communities) do you bring to your practice?

LW: I have so my pools of collaborators to cull from because I have all of these different communities I have lived in, all of these towns that I’ve formed relationships in. I think artists tend to gravitate towards like minded artists. I often curate from those communities, and have shown a lot of artists from those different chapters in my life already.

Predominately I show work that has historical significance within my own interests or contemporary work of people in my community that I feel have valuable voices.

And because of all of the places I’ve lived, I have a lot of resources.

JC: Did the desert landscape shape your practice in any way?

LW: The desert does inform how I think, without sounding like… “the desert is within us all” [laughter]. I think it was an amazing place to be in my transition into adulthood. The town had an intense class divide so it was either wealthy white people or poor indigenous people and then college students who were somewhere in the middle, but more often on the privileged side. I was there on a scholarship and working a fulltime job. I was there with other people who did have a lot of money because it was a liberal arts college. From that point, I have always thought socioeconomically about the work I make and the efforts and interests I have when it comes to art.

Within my own practice I found installation arts, and by the end of my time in school I was interested in creating environments that focused on institutional critique. For my thesis show I created an environment where you had to touch the objects, and engage and explore the space to access the work. The show was pretty basic shit looking back now. I mean I wouldn’t even show a picture of it, but it’s where I started really wanting to question the standard practice of how people engage and work with art and also the people who have access to it. And despite the troubled nature of my now defunct school and my education experience as a whole, I will say that I was there with a radical group of people who have all gone on to do really weird, interesting, and profound things. And as a community we have continued to keep each other in check with our own advancements.

Because it was a small place, you had to create your own reality because there was nothing there for you, which we all figured out early on, but because of that we learned you could make anything you wanted to see happen.

JC: In some ways not having the pressure that comes with a legacy frees you up.

LW: Yeah, I mean the college isn’t even there anymore, but the work that was done there was monumental. There are master artists, business owners, and inventors and creators that were part of my few years there and they all have successful lives in their fields. And again I would say that everyone really had to invent their own reality around what it meant to succeed as an artist. There were some really amazing artists out there because Santa Fe is such a weird scene. Santa Fe at that time was probably the Joshua Tree of right now.

It felt very wild at that time, and a weird place to be a young person. It was cheap and we were just loose to explore fucking crazy landscapes. We would party at a place called Diablo Canyon. We would take mushrooms in Diablo Canyon- imagine the implications. [laughter].

JC: What experiences from the bay area and the east coast?

LW: In those places, I worked as an art handler so I have this institutional training as far as handling, care, registration, and communication around art. It’s another layer, another fold that creates a divide within that industry. The preparators were mostly artists too. So it was a weird humbling experience for everyone who did that kind of work. It was also eye opening to know how little the artists being presented actually did at that level, a lot of the time. For example, much of the work is done by hired anonymous helpers. And just how rancid the industry gets at that level. But at the same time, most of these people go on to have successful art careers of their own and cross over to the other-side. That is a baseline job for a lot of artists who go on to have careers in the field. It’s hard to see it then- when you are doing all the grunt work. I know so many people from that time who are now very successful practicing artists.

Beyond the name Portland Museum of Modern Art, yes, this is also a challenging funny name for a space, I get to have the clout of having professional training to offer up in exchange for people who feel nervous.

JC: Yeah, you can back it up.

LW: Yeah, so that’s a bonus. It also means I know how to build and do real construction work and I was able to build my own space.

JC: At what point did you shift from making to curation?

LW: I don’t know if I have yet. I was just talking to someone about this the other day because this next show is one of the most challenging shows I have ever done. I keep feeling like this show is so chaotic and something that I wouldn’t say that I curated because it is not even really about that. So I am not sure if I see curation is the main main focus of the project. I think it’s like a default or a vein that I have to consider, but it’s just part of the package. When you do everything curation is just a part of that. I was thinking about that with Roz’s (Roz Crews) thesis project. Social Practice is really hard for me to align myself with sometimes, because at the end of the day I’m not an institutional intellectual. I wish I was sometimes, because then I would write a thesis in defense of accepting self- organized arts spaces, and of the work that goes into them, as definitive art practices. I still don’t know why it is so hard for people to wrap their head around that fact.

JC: Yes, it takes so much creative energy.

LW: Exactly. I mean why do I have to be an administrator and I don’t get to be an artist? Then I hear a talk like tonight (Roz Crews at Portland State University) and I’m like, ‘yeah those are all of the things that I do.’

There is so much thought that goes into every part of what I do that I can’t not see it as an art practice at this time in my life.

Which is why I asked PICA (Portland Institute for Contemporary Art) to present me as an artist rather than a curator.

I would say that I never really switched over. I have had curators tell me that I need to get over that. It is an interesting time to be a curator when it has been co-opted as a label.

JC: I read that PMoMA was created because you saw a gap in the programing that was being presented or the artists that were being shown in the city when you came back. What did you see or not see at that time?

LW: Well there wasn’t a contemporary art museum. I was thinking about what I was not seeing in my community. It did change a lot since I returned. The cultural center had evolved, but there was a divide within the arts community. I felt like there wasn’t an access point, so I just wanted to experiment with making the thing that I felt was missing in my neighborhood. And in that regard, I don’t think that I have succeeded yet. I think I have just crossed over into the insular Portland scene. Which might not be helping. I mean, yeah cool, I have been welcomed into this community and it feels good that after 4 or 5 years, the work I have done has allowed me to be a part of a bigger conversation, but maybe that’s beside the point. It’s not the end goal of what I’m trying to make happen.

JC: How do make sure you are challenging yourself.

LW: I think it’s about continuing to open myself up to new communities and meet people who don’t necessarily identify with being apart of the arts community and invite them into the space and create opportunities for them to have their voices present in my space. And that’s a constant challenge.

The cool thing is that I have solicited the Portland Art Museum to let me do that there. Initially they invited me to do a PMoMA at the Portland Art Museum, but for me that wasn’t that interesting. What I proposed to do was continue this same line of investigation. So if I’m trying to create the thing I don’t see in my direct neighborhood and make that my main focus then what would it look like to ask those same questions in this major institution that I feel is lacking in certain areas? And they agreed to it- so they’re letting me do this huge institutional critique project inside the Portland Art Museum.

JC: When is this happening?

LW: It’s going to start in the late fall and go on for about a year. It’s a whole series. And I will be working with different communities and giving them the opportunity to decide what a presentation looks like. So it might be a film series or performances or a visual art exhibition. I have the whole fourth floor of the contemporary art building for this.

Poster from Art from the WPA Era currently at the PMoMA

The main thing for PMoMA is that I keep asking those questions and I have to remember that I want to keep holding onto the core things that I’m asking of my own space. Sometimes that means presenting a really fucking weird and serious history blip. Which is what I am doing right now. This might be a really hard to swallow show for my direct community, but also nobody really knows about this history, which was not that long ago and people should, especially in the current political climate that we are in.

The show, The Project: Works from the WPA Era, is all art works from the Works Project Administration from the 1930s, which was FDR’s subsidized art program that paid artists to make art for like 8 years and it helped bring us out from the Great Depression. It was also essentially funding all these radical communists to make paintings.

JC: What was the process like for deciding to program this show?

LW: Since I did the Houseguest project in Pioneer Square, I didn’t program another show for the winter and I didn’t know if I was going to have my space back (in the basement of Mississippi Records). I found out that I would get the space back in the summer right before the U.S. Presidential Election and I feel that everything changed for so many people and it just felt like a really important time for reflection around what we are all doing.

Instead of thinking about what my arts programming would be, I started to think about organizing fundraising events which has been what I’ve been doing for these last few months. I have organized film screenings at the Hollywood Theatre with Eric Isaacson (of Mississippi Records) and picking social organizations to fundraise for and to also give platforms for people to talk about the civic work they are doing. I think it’s just been a pressure, a real pressure, to think about how I wanted to re-enter that art space and I know I didn’t want to just be showing my friends visual art, but to use it as a platform to talk about social issues and ideas that I am thinking about.

The WPA (Work Projects Administration) show I have been researching and developing for a long time. There is so much WPA in the Northwest and when I did a show a few years ago called, Portland Collects, it was all about different art collectors in Portland and the work they live with. A lot of the collector’s homes I visited back then had work from this era in their homes. It was something I didn’t know about and through research I began to understand what it means to have social service be something that trickles down into every household. So for example, if your household’s predominate income is from an artist then that was what they would be employed to do by the government seems so radical compared to what we are experiencing right now. But at the time it was also resisted for many other reasons. It’s not a part of the history that I am presenting in the show, but it is a really interesting part of that history.

What I’m presenting is a pretty cookie-cutter show of the administration because I think it is good to talk about federal subsidizing of arts, but really it was a lot of people who were fucking ready to start a revolution who then got jobs with the federal government to make art and them dealing with their own internal conflicts. Thousands and thousands of artworks were created after this that had no “value” because it was just being cranked out. Think right now I have been think about how looking back at history as a really great way to see social change.

So I thought it would be great to start with a historical show and the next show will be a contemporary group show about woman identified bodies.

JC: It’s great to hear about how an interest is revealed and then a project unfolds over the years. It’s as if it was in the back of your mind for some time and now you are pulling it to the front.

MR. OTIS poster from PMoMA October 12th-November 24th 2013

LW: A couple of different shows have happened that way. One of my favorite shows was a few years ago called Mr. Otis. They were paintings by Stewart Mulbrook under the pseudonym Mr. Otis, an outsider artist. That work is really hard to come by, but there is one collector in town, the Booth family, who have artworks. Gwyneth Booth let me borrow all of her Mr. Otis paintings for the show. She and her husband have a great collection of works including works from the WPA. So much of the work for this show is coming from the collectors I met years ago as well as children of the artists.

I’m borrowing from the children of these artists who ended up with all of this work, not always good work, and I say that in the most respectful way, but you end up with a thousand paintings of landscapes or thousands of brown on brown labor scenes and it’s not always visually interesting. When I pull from multiple places, I am able to create, hopefully an interesting visual experience. But again it is a really hard show. It’s a hard show for me right now to even figure out how it all fits together.

JC: One of the most difficult things as an artist is establishing the criteria for finished work.

LW: Yes. For this show it’s maybe the hardest I’ve experienced because I was very worried about not having enough artworks that I managed to get so much that it is now going to be a very dense show. I think when you have a dense show, you risk taking away the quality of the individual pieces.

For the show there is going to be a salon style wall which is incredibly difficult to pull off, but I have to do it because I want to show the immensity of the work that was created at that time. I feel like it is a really great way to convey the production during that time. I read in my research that tens of thousands of paintings were made and after the WPA ended paintings were auctioned off by the pound. Plumbers would literally buy paintings to then wrap their pipes with. People would buy them just to burn them for fires. The amount that was created during that time was just insane. So I figure if ever there was a time to do a dense show this would be it. I suppose that is part of what makes it a hard show because in some ways it goes against my aesthetic instincts, but historically I feel like it is important to acknowledge. I wouldn’t say that it is avant garde, but I would say that it takes an avant garde mind to appreciate the works I have selected.

JC: The businesses in this area, Mississippi Records, Swee Dee Dee, Red Fox, and Cherry Sprout, have really embraced and supported each other. What kind of dialogue would you say you are all having with one another?

Mississippi Records storefront

LW: I have worked with Mississippi Records since the beginning. Honestly Eric Isaacson who owns Mississippi Records has been my main collaborator since I started PMoMA. And when I say collaborator, I mean it in the truest sense. He is the person I sound off my ideas with and make sure they are wholistic and thought through. He has always made things accessible to me that I wouldn’t have known how to access, but have been interested in.

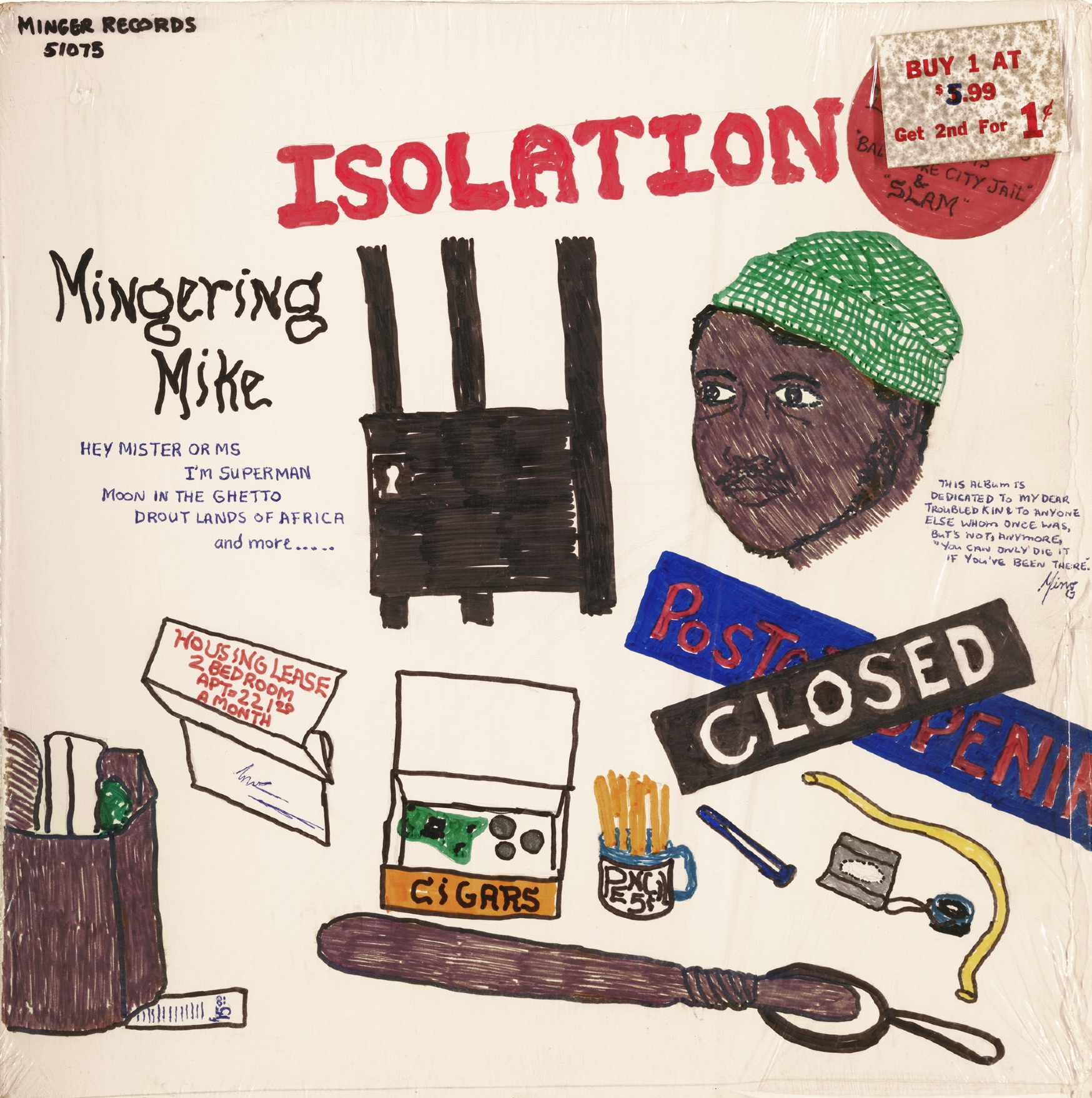

Mingering Mike poster for PMoMA show

We started the space off with Mingering Mike paintings which I have been a big fan of forever, and it has been through the success of that record store and label that I have been able to tap into a certain cultural line of art that I wouldn’t have had access to by just cold calling. His street cred has helped give me access and I have no shame in that. I think it is awesome because they are all people who value the same things as I value.

JC: That makes me think of how we spoke earlier about music being a very important, and sometimes only, tool to access alternative culture or a culture that isn’t immediately accessible.

LW: Yes, that is what Eric and I have based a lot of our relationship off of; the fact that at an early age we both realized we had to create our own access and he did that through music and collecting records. At that time records were the cheapest format of music. You could get all of it at garage sales and thrift stores for really cheap.

He started a label that has gone on to be very successful in part because records are popular today. It wasn’t exactly that way when he started. He wanted to create an opportunity for the artist to make money from the albums they made. He has worked with people and made sure the money goes directly to them, even if they have big record labels.

His business ethics have really been an important model for me. When we talked about opening up my space in that building, it was an extension of that model. We were thinking about how we can operate with the best practices within the arts in the same way he has been with the label. That’s why PMoMA is not a commercial space. We sell art if the artists are interested in selling the work, but I work with artist individually to figure out what commission looks like for the space and it all goes back into the space.

It has been a huge resource to work in this community. I have a restaurant upstairs who feeds me and my artists, a grocery store across the street for opening refreshments, and a bar to go to after a long day of install or after the openings to continue conversations. We all support each other and create opportunities for each other and it’s really magical. I really can’t imagine this existing anywhere else. That doesn’t mean that I won’t go off and explore my own questions and interests in exhibition curation or space making, but I feel like people know that PMoMA was something that was created specifically to live here.

JC: What questions are you exploring for the next season.

LW: This year I want to be exploring and presenting themes that are important to me right. Again, looking at various histories and alternate versions of the future that the mainstream is not presenting. In general, many of us are drawn to and responding to these doomsday future options. That is what feeds us and perpetuates our fears and it’s what keeps me up at night so I really want to look at different artists or movements who are working with better or more utopic versions of the future.

I have been thinking about what tomorrow looks like without fear.

I’m working on a Sun Ra show. He has been a major role model for artistically expanding your mind to think about our bodies’ role in the future. And the Cockettes who were a queer theater group in San Francisco in the 70’s. With that show I’m thinking about how people, as we’ve been discussing, create their own realities because there was not one for them, and how fast the world responded to that, to them.

The next show is a personal show. A lot of spaces are wanting to show women artists, but they are not always spending enough time thinking about women identified artists. The next show I’m hoping to open up that dialogue a bit to think about what woman identified means. It all comes together for me when I think about the future as this non-binary pan reality for my own utopic vision.

Jodie Cavalier is an interdisciplinary artist working in Portland, Oregon. Cavalier received her BA from the University of California, Berkeley and MFA from Pacific Northwest College of Art in Portland, Oregon. She has participated in residencies at; the Center for Land Use Interpretation in Wendover, Utah in 2014, Wassaic in 2016, and AZ West Wagon Encampment in 2017. Her work has been exhibited at the Schneider Museum (Ashland), the deYoung Museum (San Francisco), Pacific Film Archive (Berkeley), CoCA (Seattle), EXO Project Space (Chicago), Städelschule (Frankfurt), among others. A new body of work will be on view at Anytime Department in Cincinnati this July 2017.